by Ruth Uyesugi

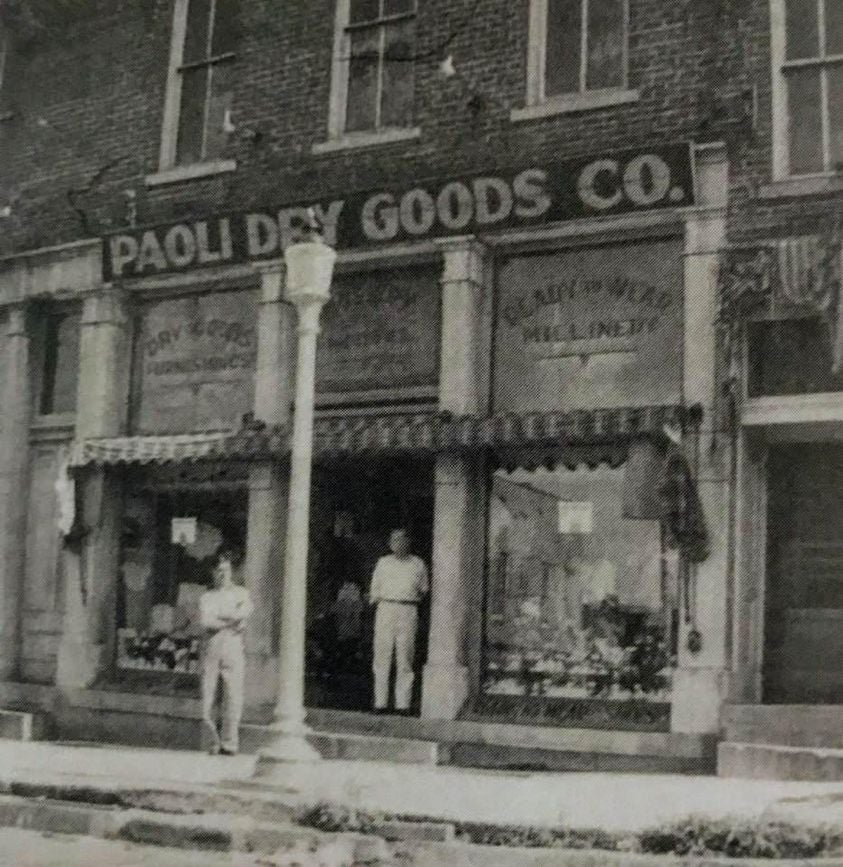

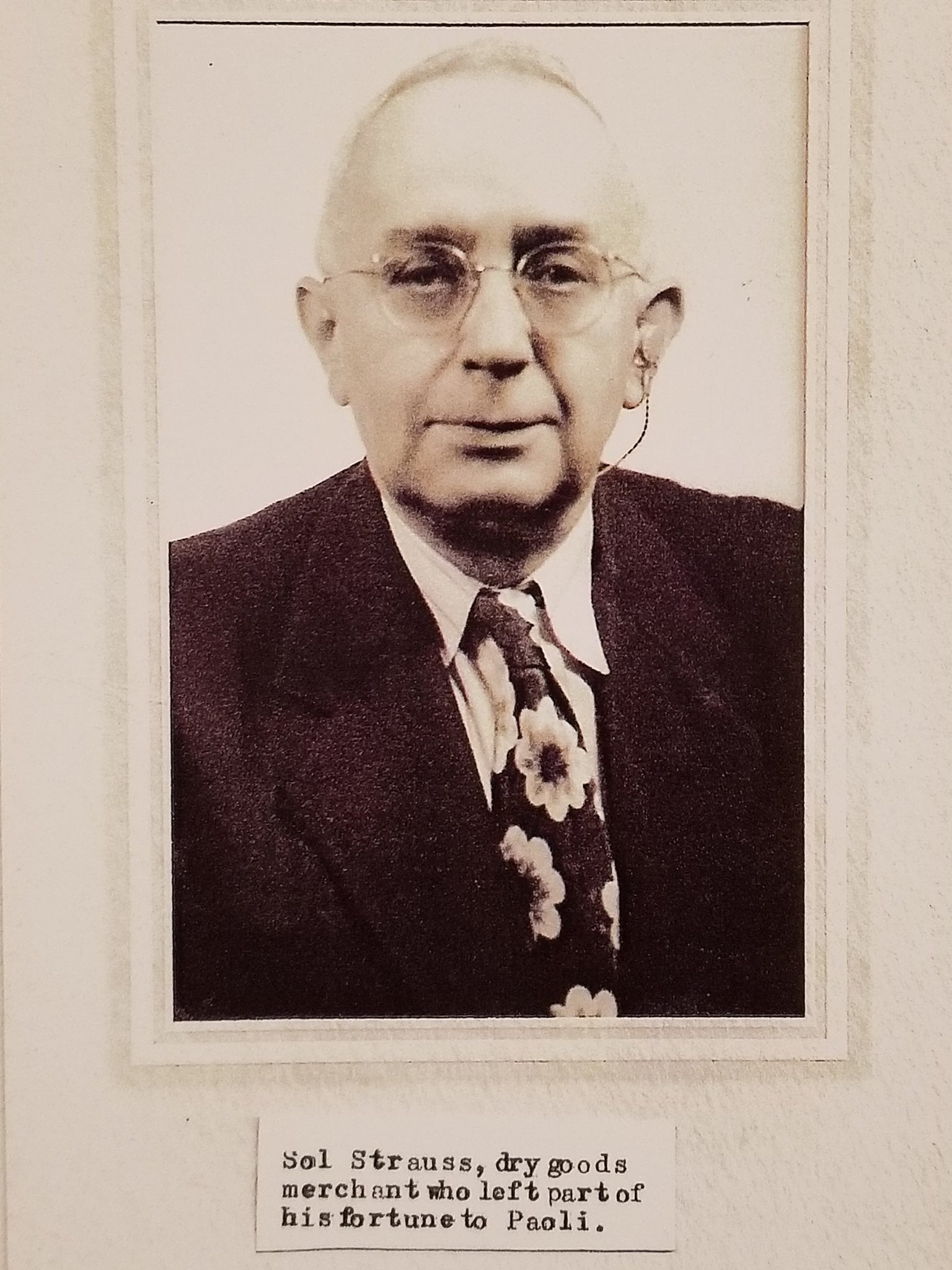

“The following article first appeared in a publication of the Paoli Friends Church. Paoli is a very small southern Indiana community. Probably Sol Strauss and his mother were the only Jews who ever lived there. The story of what this solitary Jew did for his adopted town is heartwarming and is a part of Indiana Jewish history. . . . “They called him the Jew. For over a century this stubby, scratchy-voiced man operated a dry goods store in the small southern Indiana community of Paoli. His name was Sol Strauss, but few people bothered to pronounce it correctly, so he became known as “Stross.” Behind a rainbow mountain of yard goods, he furnished the townspeople with everything from buttons to boots. It was the poor man’s store. If a housewife wanted an everyday dress, she could buy the material for 10 cents a yard. If she needed a real Sunday-go-to-meeting model, she could go as high as 19 cents a yard. The whole outfit, plus thread and binding, would cost about 87 cents. A German Jew, Sol immigrated to the all-white, Protestant community of Paoli following World War I. He had served in the German Air Force, and when his country began to rebuild its fighting machine, Sol decided he had had enough of war. Some people in his adopted town thought that Sol had bombed “our boys” and, consequently, wouldn’t shop in the “Jew’s Store.” In reality, Airman Strauss had worked with a truck crew that salvaged wrecked planes. Everyone agreed that Sol was a lonely man. In the evenings when others were swinging on the front porch with their neighbors, he had to find his own kind of relaxation. He would walk around the town square, sometimes going as far as the city limits. “He probably wants to spy on our window displays,” scoffed rival merchants. Although I was a child when Sol was a part of Paoli, I, too, have to share the blame for his loneliness. Did I ever smile at this little man? Did I ever try to enter his myopic world? Probably not. Most people didn’t make the effort. That’s why for weeks I have wandered through the streets of Paoli asking those I meet, “Did you know Sol Strauss? Can you tell me who he was, what he was?” A beauty operator said, “People were very prejudiced, insensitive to him, and he learned to live with it.” A businessman confided, “He really didn’t want companionship.” A merchant who perhaps knew him best rationalized, “He didn’t know anything about baseball or politics so what would I talk to him about?” An employee of the “Jew’s Store” observed, “He thought he was an outsider. He knew his place.” Another clerk who remembers that Sol forgave her even when she sold two right shoes to a customer said, “I feel bad that I never made any effort to know him.” For many years Sol lived alone above his store in an apartment about thirty feet square. Once a month a messenger delivered a large box of German bread to his door, and this, along with bologna and eggs, was his fare. When a second world war threatened, Sol knew he had to get his mother out of Germany. Aunts, uncles, and cousins disappeared into the gas chambers of Nazi concentration camps, but Sol brought Mama to safe, secluded little Paoli. Not being a bitter man, he didn’t like to discuss Hitler, although one person remembers him saying, “That man’s crazy. He’s power-mad.” No doubt his mother made him lifelessly lonely, but her inability to read English almost brought her son to a tragic end. Because he had a morbid fear of rats, Sol always kept a supply of poison. Probably mistaking poison for garlic, Mama once seasoned his bologna sandwich quite thoroughly. “It made me sick for three or four days,” Sol admitted. Sol was serious about his business and personal life. He didn’t like to joke and never quite understood the jokes of others. One acquaintance remembers meeting him in the post office to pick up the early morning mail. Leafing through a large stack of junk letters, Sol grumbled, “I don’t see why I get so much mail.” The other merchant said, “You know how to cut that mail down?” “How do you do it? How do you do it?” Sol asked eagerly. “If you pay some of those people, they’ll quit writing to you,” came the teasing reply. A miffed Sol shot back, “Young man, you take care of your business, and I’ll take care of mine.” Then there was the time in the local cafe when Sol announced to the same man, “Today I buy you coffee.” Unable to resist a little joke, the friend said, “And I think I’ll also have a piece of that apple pie over there.” Sol blustered quickly, “No, no–no pie, just coffee.” The average person in Paoli probably assumed Sol was a miserly man, but the grieving, the sick, and the poor knew differently. They were his welfare children. During the depression, a twelve-year-old girl began her first babysitting job. The pay was $1.50 for a six-day, sixty-hour week. Since she possessed only two dresses and very little to wear underneath, the child went to the Jew’s store to buy on the lay-away, pay-weekly plan. Evidently, Sol noticed that she always seemed to wear the same outfit when she came to pay, because, after the third week, he said, “Honey, I think you need clothes now. You take them, pay later.” Sol didn’t advertise his generosity. In fact, at Christmas time, churches and civic organizations often received anonymous gifts for the needy, but no one dreamed that they had come from “Mr. Stross.” Fires and funerals were of particular concern to Sol. If the poor needed clothes to wear to a funeral, they could borrow them from the “Jew’s Store.” And when there was a “burn out” in the area, he would tell one of his clerks, “Fix them a box. They’ll need blankets and towels.” But he would warn the employee, “Don’t say anything about this.” One of Sol’s clerks recalls the night she took her husband 100 miles away to Indianapolis for emergency surgery. By eight o’clock the next morning, her boss was on the phone demanding to be allowed to help. Although the lady protested that she could handle the debt by cashing in an insurance policy, in three hours a courier arrived at the hospital with $800 to cover the bill. Doubtless, there were those in Paoli who considered this graduate of Heidelberg University a simple, unimaginative man. But they were wrong. Sol had a hobby, a game he could play in his isolation. During the depression years, he bought blue-chip stock–AT&T and General Motors. Then he watched it grow and grow. Even in Paoli citizens didn’t accept their Jewish import, he accepted them. A local attorney who shared his confidence remarked, “This man loved Paoli. When he would go to New York on a buying trip, he would say, ‘My people are poor people. I got to buy bargains for my people.'” If there was any forgiving to do, Sol evidently turned the proverbial another cheek. When he drew up his will, he told his attorney, “These people have been my customers all these years. I’m going to fix it so they will benefit.” When he died in 1960, this Jewish immigrant left to the town of Paoli a legacy, 30 percent of the interest on a trust fund of over $300,000, a sizeable estate for those years. The Orange County Hospital received 40 percent, and the Jewish Hospital in Louisville, 30 percent. Because this lonely man loved his town, Paoli Little Leaguers have uniforms, the Boy Scouts are the best-equipped in southern Indiana, English classes read books they could not afford to buy, a children’s library was founded, the 4-H Center was improved, the volunteer fire department has new equipment, and last year, with the help of the “Sol Strauss Fund,” the town pool was repaired and opened on schedule. And the giving and receiving will go on forever because of a little Jewish man that no one really knew.”